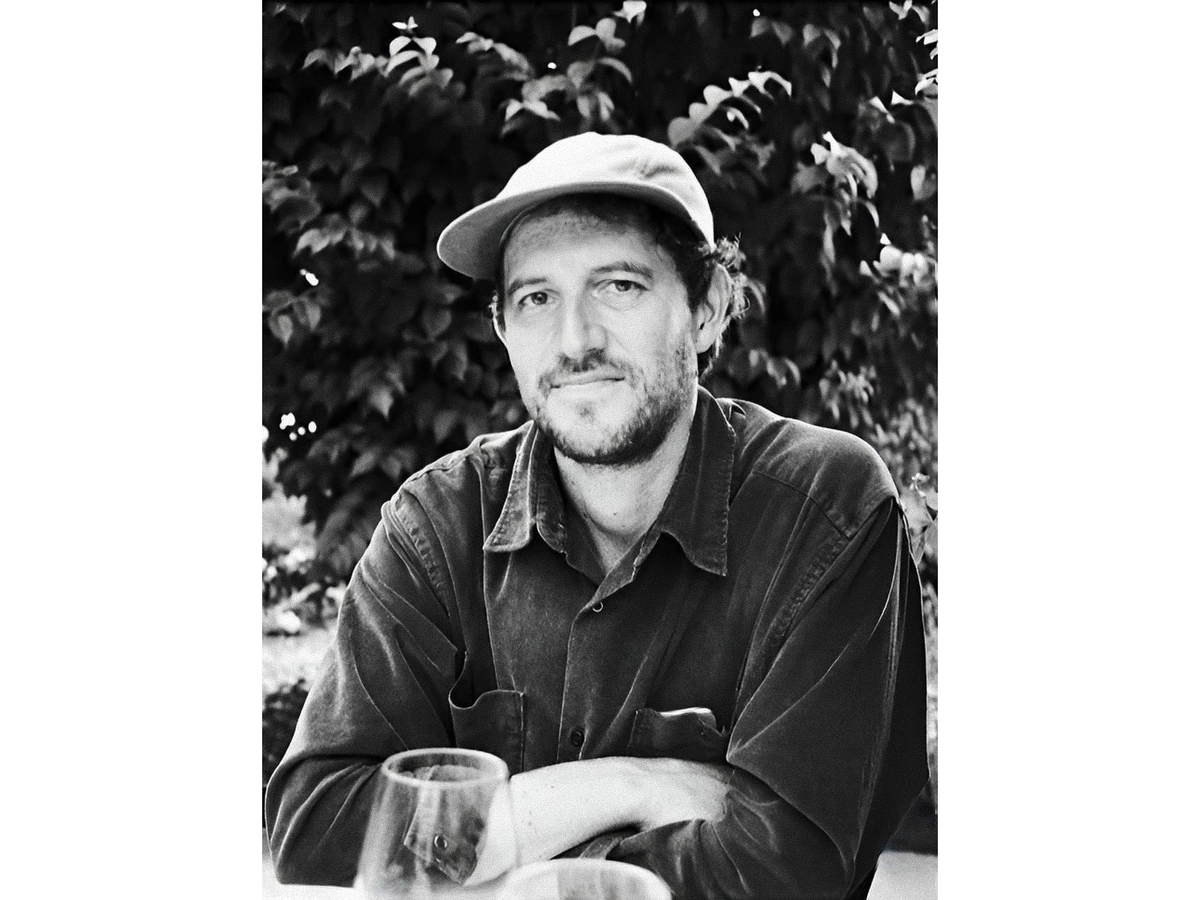

MAGNUS ZACKARIASSON TALKS DESPITE EVERYTHING WE PLAY IN THE WIND

"Working with words is what matters most"

This book is published through your own publishing house 2066, which is set to exist for fifty years, what will happen after that?

If everything goes according to plan, I’ll be dead by then. In 2066, I’ll turn ninety-four, I’m aiming for a hundred, though.

What’s it like running your own publishing house?

It’s the perfect way to spend time with my good friend Kuba Rose, who I share the imprint with, and beyond that, most of the work fits neatly on a simple to-do list, which I try to get through as quickly as possible.

Do you have any particular vision or ambition for what you want to publish?

We publish photography, poetry, and essays, without any kind of over-arching guideline, strategy or manifesto beyond our own subjective preferences.

This is the second book you put out, the "2066:2" catalog-wise. What was the first?

2066:1 is called 'Becoming Somebody', a photo book by Kuba Rose that documents twelve specific actors as they step into their roles on the theatre-stage. That book also includes an invigorating essay by Leif Zern.

Do you know what book 2066:3 will be?

2066:3 takes its starting point from 'Aniara' by Harry Martinson and will feature photographs by Kuba Rose, as well as two essays. One by the poet Anna Hallberg and one by the astronomer Bengt Gustafsson.

What were you doing before starting the publishing house now two years ago?

I was mostly writing journalism, which was wonderful, meeting so many fascinating people.

What possibilities come with running your own publishing house that, say, self-publishing doesn’t offer?

The main-opportunity lies in writing a few words on a piece of paper, then seeing if they hold up, or if they should be changed or deleted, and then doing it all over again. That is the whole point for me, the rest is just circumstance.

Has literature always been part of your life?

For as long as I can remember, my beloved aunts would call out, “Magnus! Do you not want to come outside for a bit?” while I lay peacefully on some sofa reading, which really means I could have been anywhere in time or space, and it’s not always so easy to snap out of that, even when juice and cinnamon buns are being served.

When did you start writing your own words?

I must’ve been around twenty, sitting on a sun-warmed rock by the Kungsbacka–fjord, writing something like, “Now I’m going to start writing” in a black notebook I’d gotten from my then-girlfriend, who was impossibly wise, probably having concluded that I should think through my days a bit more carefully. Or, maybe, she had just heard me say I wanted a notebook.

Are there any writers whose work you just especially enjoy reading?

There's so many, but if I have to name just a few, Yoko Ono’s 'Grapefruit', Michael Lewis’s 'Flash Boys' and others, Sara Granér’s 'It’s Only a Little Aids', Lars Gustafsson’s 'The Library', 'The Silence of the World Before Bach', and 'Where the Alphabet Has Two Hundred Letters', Henry Miller’s 'Black Spring', Tom Wolfe’s 'The Bonfire of the Vanities' and 'The Feature Game', the poetry of Li Po, Tomas Tranströmer, Bruno K. Öijer, and Catullus, as well as Werner Aspenström’s 'You and I and the World', the writings of Edith Södergran, and of course Nabokov’s 'Speak', 'Memory' and his work on Gogol.

Is writing more of an in-the-moment process for you, or something more deliberate and focused?

I think my ideal is a conscious and well-structured writing process, and I like to sit for a few hours every morning and write. But it can’t be helped, sometimes, anywhere, an idea comes that I have to jot down, usually with a borrowed ballpoint pen on a crumpled receipt. Still, I don’t really like those notes, and I rarely even try to decipher what I wrote.

Why write poetry?

Working with words is what matters most to me, and I don’t see much difference between, say, poetry and prose , except that far too many novels seem to be written without the humility to follow the old advice of cutting everything that can be cut. I have tried to avoid generalizing themes, but there are patterns and symmetries that, at best, might shimmer faintly, for the reader. Above all, I love being carried along by a good metaphor. And since I try to write realistically about everyday life, what I truly experience, I see metaphors as absolutely essential. Not just because the brain seems to understand the world through analogy, but because "the metaphor" is just such an effective tool for breaking free from both dull clichés and conventions.

What makes a good poem?

It should ideally offer something new, beautiful and true. Many of the poems use metaphors drawn from everyday life.

Do you have a favorite poem from the book?

Not really, but just of the top of my head I think of this one, "In the escalator’s rise, the city’s glow, worlds folding into each other".

Was there one you weren’t so happy with but included anyway?

Now that the poems are printed, I try to accept them all as they are, including that four-liner I actually called the Gothenburg printer about, asking if they could replace it with a blank page. They said they could. For a price. In the end, I let it stay as a reminder that I should probably give whatever text I’m working on just one more look.

When do you feel your poems are best read?

Anytime, they’re there whenever the moment might suit.

Won’t it feel a tiny bit sad to put 2066 to rest when that day, eventually, comes?

Probably, but it will also be nice to take it easy for a while.