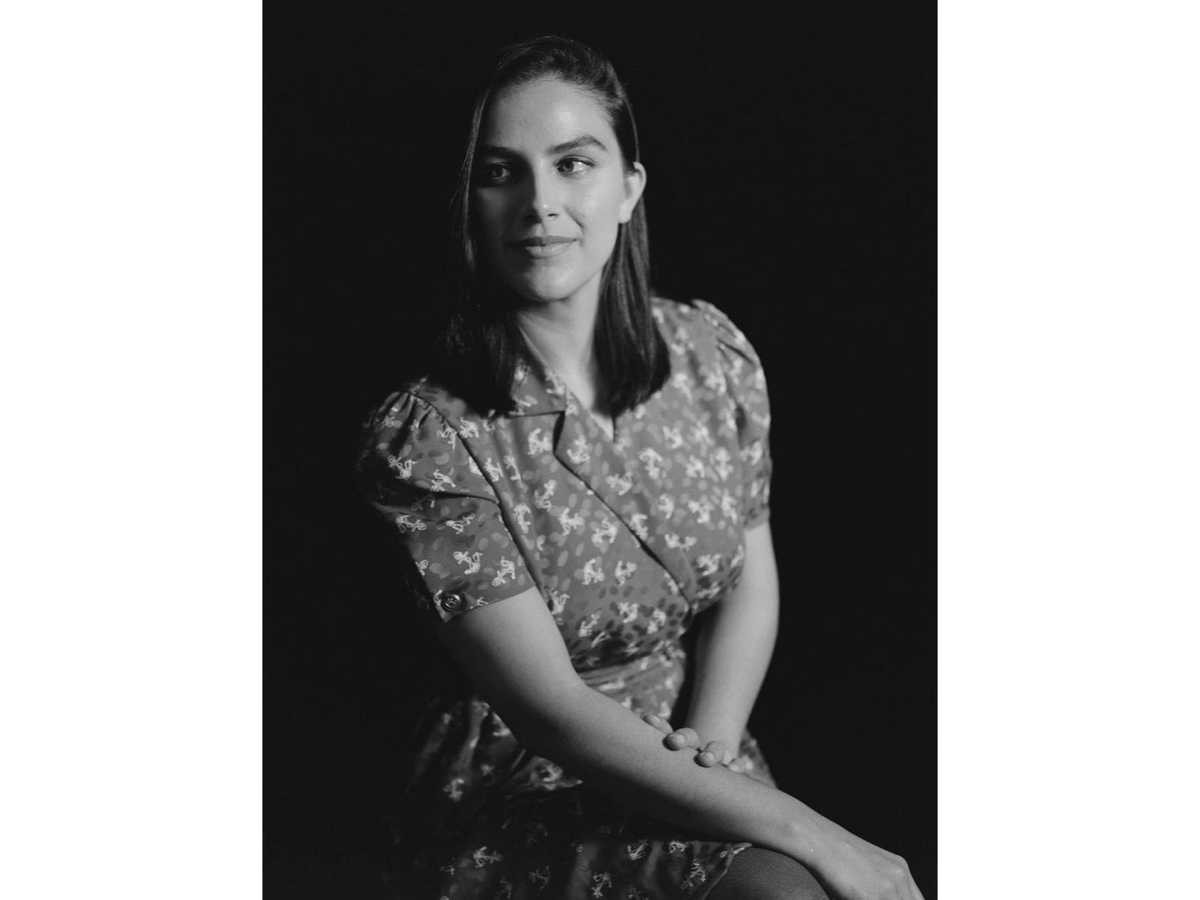

NATASHA KERMANI TALKS LUCKY

"There’s insidious inequity to the industry"

You started out working on others’ films, but quickly made your own. This year marks ten years since your first short, 'The Turning Love Affair'. Why have science fiction and horror drawn you from the start?

I’ve always been drawn to science fiction and horror simply because I love getting lost in fantastical worlds. The stretches of imagination on display was always what drew me in, the sense of seeing something new and different, and now, as a filmmaker, it is the opportunity to create new worlds that draws me to genre projects. The ability to bring a story to life using such bold, heightened colors is something uniquely exciting about working in the genre space.

What made you want to pursue life as a filmmaker?

I was fortunate enough to be exposed to the arts at a very early age, my mother is a musician and a multi-media artist. I also fell in love with cinema early on, primarily due to my father’s love for movies and the bond we formed watching all sorts of science fiction and action films. Once I realized that one could make a living and a career out of "making movies" I knew that was the right path for me.

Have there been any particular directors that have inspired you and influenced your own work?

There’s certainly a myriad of incredible filmmakers from all different eras of cinema from whom I’ve learned so much, from silent-era Fritz Lang films to modern works by filmmakers like Kathryn Bigelow or Park Chan-Wook. Tarkovsky is someone I find myself constantly returning to, especially his writings on film, and of course Kubrick’s films especially '2001' and 'The Shining'. I also draw a lot of inspiration from other art forms, especially classical music and fiction writing in the genre space, like Clive Barker or William Gibson, and when I’m going into a new film I actually try to avoid being over-exposed to similar films so that I can “find” the piece myself in a unique way, rather than creating something that might feel contrived.

Is it right ‘Imitation Girl’ directly led to the ‘Lucky’-script falling onto your lap?

I suppose you could say that! 'Imitation Girl' was acquired by Epic Pictures as part of their "Dread"-slate, and shortly after our release, one of the producers, Rob Galluzzo, who was working at Epic at the time, sent me the script for 'Lucky', he had a feeling that I would respond to the material. Which I did!

You actually emailed the screenwriter personally after reading the script, saying you wanted to be part of it?

I did email Brea after reading 'Lucky', we knew each other socially at the time but had never worked together. I sent her a short email saying that I had a very strong reaction to the film and felt it was important that the film be made. The script had a strong point of view, and while it has a heavy theme, brought the reader in with a very light, satirical tone, which I found very unique and to be an interesting challenge to approach as a filmmaker. Ultimately though, my interest in the script came from the way I felt that Brea had captured a universal experience, and my connection to that experience. I felt that I understood what she was trying to say, and that I could bring it to life.

Was the director-actor relationship different due to Brea also being the screenwriter?

Working with Brea as both the writer and the star of 'Lucky' was not problematic, I think the key for us was to establish trust right from the get-go. Once we felt comfortable and there was a real sense of teamwork and aligned vision for the project, we were able to really move forward without any issue of ego or competition getting in the way. Brea is a true professional, and I think she trusted my vision for the project and was able to focus on the work she had in front of her as an actor, the role she plays is very demanding physically and mentally, so she had her work cut out for her!

Did you audition Brea for the role?

No, we did not audition Brea, she actually hadn’t envisioned herself in that role, at first! But she was open to it, especially once we had discussed how the film might come together. It was so helpful to have Brea at the center of the film, especially with how “indie” of a production it was, to know that we could build everything else out around her as May.

What did you make of May the first time you read this screenplay?

I find May to be incredibly complex, which drew me in, May doesn’t always make the right decision or do the right thing, which I think makes her feel very real and relatable. She makes some problematic choices throughout the film, and struggles to connect with the characters around her and even the world around her. I think Brea brings a warmth, humor and humanity to May that was absolutely essential - because without that charismatic quality that Brea inherently has, May could have come off as being quite cold. As I was reading the script, I was envisioning Brea in the role, which also really helped me imagine the character coming to life.

John Carpenters ‘Halloween’ was notoriously shot in only twenty days but you did ‘Lucky’ in only fifteen days. Is that as intense as it sounds like?

Yes we filmed 'Lucky' in fifteen days, it was very tight and as you can imagine included a lot of compromise. There’s never enough time on a feature film shoot, but this was definitely a huge challenge for us and every single department had their share of problem-solving and creative workarounds. We did our best to preserve the sequences that really needed resources, for example the parking garage sequence, knowing that saving time and money for those sections of the script would mean having to pull from others. Fortunately, we had an incredibly talented and hardworking cast and crew who all pulled together to accomplish what we needed. And I am so grateful for their hard work and creativity!

What easily could have been a trope driven slasher instead becomes a Natasha Kermani film. An unhinged descent into a twisted nightmare. How did you approach adapting the script to your pacing and visual language?

I like to build what I call “maps” off of a script when I start to break it down, the map moves through the emotional journey and outlines how the main character’s objective drives her through the core conflict, or the “driver” of the movie. Once I’ve identified those elements, I can start to let my imagination go down the corridors of that map, that is how would this emotional event be best expressed visually, or how do I “see” it in my mind’s eye? It’s a very organic process, very free-flowing, once the “rules” of the movie have been established. Once I have a basic shot list and understand how the sequence should flow, I’ll bring in the department heads, starting with the cinematographer. We had an incredible director of photography on 'Lucky' named Julia Swain who is one of my favorite collaborators. Julia is incredibly technical and practical, but always looks at sequences from an emotional standpoint, and asks important questions about how we could better capture what the main character is experiencing. We establish which colors, lighting techniques, and camera movements, my favorite, are associated with which characters, themes, or locations, and from there the movie starts to really take shape as the puzzle begins to fit together. Finally, we are always playing the game of “what resources can we commit” versus “our dream technique” which ends up dictating how scenes are covered. At the same time that we are determining how the scenes will be covered, I’m starting work with the composer, and in a similar fashion deciding what our “palette” will be, which instruments, sounds, and rhythms are aligned with which characters, moments, and so on. It’s really a game of getting specific during prep, answering as many questions as we can beforehand so when we are on set or in the recording studio or in the edit bay, we can feel free to play within the parameters set by that very first “map” of the film.

There are some details that are not necessarily explained or at least not written on the nose. Can you perhaps talk some of the female-imagery we see throughout the film. Is there any special meaning behind it?

The production designer, LB Minnich, and I loved the idea of using imagery of the female form throughout the film in various stages of violence or disfiguration, these images were present in some of the earliest mood boards that she and I developed together. This manifested in a variety of ways, from headless mannequins and disembodied hands throughout May’s house, the hands, by the way, indicate which day we are on, as The Man continues to return over and over again, to paintings which actually change throughout the course of the film, starting more peaceful and innocuous and ending with violent, torn imagery of female torsos, often headless or skull-like, out of control. The idea was that May’s house is a nightmarish parallel to what is going on in her life, things change throughout the course of the film, from the artwork to a growing ivy-like plant that becomes more and more thick throughout the film, wrapping around the staircase, windows, and furniture.

Did you have any particular inspiration for The Man?

The team talked a lot about The Man, of course, and one specific inspiration we loved was Mads Mikkelsen as Hannibal Lector in the 'Hannibal' TV show. We loved the idea of this slightly posh, well dressed man, sort of the anti-Michael Myers, who could be, really, anyone underneath the mask. Not particularly intimidating at first, or grotesque, but rather a small, nudging feeling that something is not right about him, something is off about his face. We loved that approach as it felt more appropriate for the story we were telling.

What begins as a nightmare grows increasingly absurd and even darkly funny. Brea Grant has said the story draws from her own experiences, reflecting how many women face situations so surreal they can only be endured with humor?

The humor in Brea’s script was one of the things that I found the most intriguing while reading for the first time, and I was fascinated by the challenge of making a film that would start with this satirical tone that welcomed the audience to chuckle, but then could transform in tone so we feel the gravity of the film’s themes and core conflict. I think of the film as a piece of absurdist cinema, a satire in the tradition of 'The Twilight Zone', a piece that is meant to start conversations rather than offer any sort of resolution or solution. To me, Brea’s choice to incorporate humor was exactly the right way to invite the viewer into May’s world and the absolutely insane situation she finds herself in, and exactly the right mirror to our own world, where we find ourselves wondering, am I the crazy one? Or has the whole world gone crazy around me?

As announced by the Academy this year they are making a power move to make cast and crew be more diverse moving forward, although it can still be argued these changes are still not made to make for more diversity in the board rooms. How aware are you of the diversity of your films?

I am very aware of prioritizing diversity in my films, primarily because I want my films to reflect the reality that I’m living in, which is diverse. I’m not sure that I applaud the idea of regulating anything in cinema, and I can only speak for myself, but I do want the worlds that I’m putting onscreen to full and three dimensional. I don’t live in a homogenized world, so why would the worlds I am painting look homogenous. Unless there is a specific reason for there to be a lack of diversity, I will always open that conversation up during the casting process. The same goes for behind the scenes, when hiring department heads, and so on.

Have you ever experienced any prejudice or discrimination?

Every woman working in this industry has experienced some form of sexism at one point or another. Whether or not we actually realize it in the moment. Overall, I’ve been fortunate to find male collaborators who are similarly committed to making sets more balanced, and will continue to promote fellow women-identifying filmmakers whenever I can. There’s an insidious, deep rooted inequity to the industry at large, especially in the genre space. Women belong in horror and science fiction. We’ve always been at the forefront of genre, think Mary Shelley, or Thea von Harbou, who wrote 'Metropolis', and it’s about claiming that space. I often think about a photograph from 1994 that features George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorcese, Brian De Palma, and Francis Ford Coppola sitting together at dinner, and I look forward to the day that I can sit at a table full of women who are making their films and sharing their stories to the world as collaborators and artists.

Sweden has kept its film industry moving while much of the world stalled, with many American productions already shifting abroad for cost reasons, restrictions may push even more overseas. How do you feel about the current situation in Hollywood?

Things are very difficult and uncertain right now, absolutely. I actually just wrapped a four-day commercial shoot here in LA, and while we felt safe and the production took all necessary precautions to keep us healthy, it was very clear that indie films are going to really struggle with our “new normal” for film sets. Regardless of what the next few months bring, we must all be sure to maintain standards of safety for our productions. I am hopeful that we can continue to adapt and find a way through this pandemic, but the last few months have been an unmitigated disaster on the part of our country’s leadership and even the leadership within our industry, and that is certainly disheartening.

Do you hope to work together with Brea Grant again sometime?

Absolutely. We are always throwing around ideas and materials, so I’m hoping that day comes sooner rather than later! She is an incredibly talented woman. And I feel very "lucky" to consider her a collaborator.